Finding Failure Inside Lithium-Metal Batteries

Sandia scientists find that what goes through the separator in a lithium-metal battery during the charge/recharge cycle is more like a snowplow than a needle.

Lithium-metal batteries have potential in automotive applications because of their ability to store as much as 50% more energy than lithium-ion batteries. But their deployment is hampered due to issues related to failures such as fires and explosions. For this reason, a team at Sandia National Laboratories decided to look into lithium-metal batteries – literally.

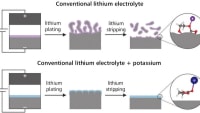

The Sandia scientists, collaborating with personnel from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., the University of Oregon and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, worked to determine just how short-circuits occur in lithium-metal batteries. The notion had been that lithium dendrites would “grow” through the polymer separator used in the battery, resulting in the short-circuits when the separator is breached by the dendrites, which would act like spikes puncturing the barrier.

To check this, they used a microscope incorporating a laser. This instrument allowed the researchers to create a hole in the coin-style batteries (the type used in a typical electric garage-door opener) then put an electron beam thorough the hole. The beam would bounce back onto a detector so that the team could determine what was going on within the stainless-steel casing. The batteries under inspection were held in a fixture that kept the liquid electrolyte frozen at temperatures between -100 and -120°C (-148° and -184° F).

The batteries analyzed were charged with the high-intensity current characteristic that is used for electric batteries, then discharged. The cycle was repeated with batteries undergoing different rates of cycling. The researchers discovered that rather than spikes, what is known as a “solid electrolyte interphase” was created. This didn’t penetrate the separator, but instead tore holes in it during the recharge cycles. As Sandia battery scientist Katie Harrison described it, “The separator is completely shredded.”

While the failure mechanism is different than the dendrites penetrating the separator, is there sufficient similarity between a commodity coin-type battery and the Li-ion batteries used in electric vehicles, to draw conclusions about the effects of fast-charging on EVs?

“Absolutely,” Harrison responded. “But the biggest similarity is arguably that neither garage door openers nor electric vehicles can currently use rechargeable lithium-metal batteries because of the safety risks they present. Our research examined the failure mechanism of this type of battery at high-charging rates precisely because fast-charging is such a sought-after property for vehicle batteries.”

She explained that although the coin cells studied by Sandia are significantly smaller than typical cells used in EV battery packs, the failure mechanisms her team reported are “still expected to be relevant to larger-scale batteries and scaled-up batteries relevant in size to electric vehicles may even be more likely to suffer from these failure mechanisms due to the larger potential for inhomogeneities in larger cells.”

Knowing the root cause of battery failure can allow engineers to take the appropriate countermeasures for what is actually happening inside the batteries.

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsAutomotive

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

ArticlesAR/AI

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

Road ReadyDesign

Webcasts

Semiconductors & ICs

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Power

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

AR/AI

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility