Physical Designs by Artificial Intelligence

Using artificial intelligence (AI) as a key tool to both interpret and accomplish custom design needs remains in its infancy. However, if our partnership with NASA is any indication, we are on the edge of a massive change in the way engineers use AI’s immense computing power to develop CAD models for critical applications. This paradigm shift will resonate for years to come as industries such as aerospace, medtech, and consumer electronics, find ways to harness this new technology to speed iteration and go-to-market times.

A quick spoiler alert: Using AI still requires well-considered human input to make it all happen and it demands digital manufacturing to do it quickly.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is in the thick of developing parts and assemblies that will be used during the Artemis mission. The project’s aim is to put humans back on the moon and eventually transport them to Mars. Design efficiencies are critical to mission success. In this case, it was all about speed from concept to physical parts that incorporate specific design needs. Those requirements were put to the test at a recent PowerSource Global Summit — a technology conference held in Orlando, Florida.

Iterating in Record Time

NASA’s exciting new spin was to challenge the existing paradigm regarding how we develop part designs. The legacy model that’s been used for decades was to create a design, manufacture, test, and evaluate the part, then send off a new design that addresses any issues with the original design. That iterative process would repeat until a final part was made—and it often took weeks or months.

At PowerSource, NASA put a form of AI called generative design to the test. “Generative Design is an iterative design process that generates multiple design outputs based on input constraints,” explained NASA’s Ryan McClelland. The experiment required building a hypothetical part for a future Artemis mission that could support an inverted 250mL container, which would be used to capture volatile compounds from the surface of the moon. These chemicals are released from the frozen surface after sunrise when the sun’s unfiltered light rapidly warms the moon’s regolith as much as 260 ºF (147 ºC).

NASA turned to conference attendees to crowdsource the design parameters based on information the agency provided to the engineers. “We’re actually taking the requirements of what does this thing have to do and what environment does this need to survive in and building the structure from there,” said Matthew Vaerewyck, aerospace and generative design engineer for NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Among the most important parameters were that the material be both lightweight and strong. Also, it had to function in an enormous range of temperatures without becoming brittle from cold or melt/expand due to heat. To that end, attendees selected Aluminum 6061, which is truly the optimal material for this application due to its:

Easy machineability

Excellent thermal conductivity and uniform distribution

Good strength-to-weight ratio

Ironically, when flying into the vastness of outer space, spacecraft storage is at a premium. Also, weight is critical. Every kilogram (2.2 pounds) of weight brought aboard a spacecraft costs $1 million in added fuel expenses, and there’s no option to fly economy. Two requirements NASA provided were that the design had to yield stackable parts able to fit into a space no larger than a shoebox.

Despite its small size, the part had to be durable, but in ways that are atypical of earthbound design considerations. The part’s base modal frequency had to exceed 100Hz. Given the effects of a rocket’s low frequency rumble on everything inside it (often at frequencies below 100Hz), that specification is crucial to part survival as it indicates that the part’s resonant frequency is higher than the spec. Resonance has to do with how a part interacts with vibration frequencies surrounding it. If its base modal frequency was lower than 100 Hz, there is a chance that those rumbly sounds could create more intense vibrations that could affect a part’s integrity. 100 Hz is a commonly used specification to describe the top-end of the rumble that could negatively affect a part during critical moments, such as liftoff and engine separation.

Other considerations included ensuring that the part had three legs, providing a stable platform just in case the device was placed on an uneven part of the moon’s surface.

From Concept to Manufacturing

After several hours of discussion amongst the engineers, the specifications were locked in. NASA then input that information into their own proprietary generative design application, which quickly provided a suitable CAD model. Before going into this project, NASA had no idea how AI would model the device. Interestingly, the model the generative design produced was considerably different from anything a person was likely to have come up with on their own but was also entirely sensible and functional for this purpose. The process of moving from conceptualization to model took ten hours. Once completed, the CAD model was digitally sent to Protolabs for quick-turn machining using digital manufacturing.

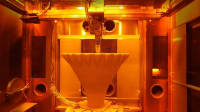

After a quick design for manufacturing analysis by our applications engineers, the CAD file was uploaded for machining approximately three hours after the generative design of the part was complete.

The next step was translating design into G-code for toolpathing — a process that interprets the CAD model and defines the most accurate and efficient way that end mills (often more than one type and size is used) should cut through material using CNC machining.

The process from toolpathing to complete machining of the part out of a block of Aluminum 6160 took 19 hours to complete with the part compete leaving our CNC machining facility in the early evening hours the following day.

Then, the part was shipped for overnight delivery.

Arrival and Proof of Concept

Early in the morning — and only 36 hours after the order was placed — the NASA team were amazed and ecstatic to have the part in hand. What was merely a set of generalized parameters detailing what the part needed to do and what it needed to survive in the moon’s harsh environment turned into a physical part, ready for display at the conference.

In the end, NASA and Protolabs were able to prove the merits of combining human intuition and AI-based design-building with the speed that digital manufacturing is known for. In the future, this will make it easier and faster to iterate parts and even reduce the time required to conceptualize them.

“What we’ve seen with generative design is a 6-10x improvement in multiple different avenues of mass, stiffness, and design time,” said Vaerewyck. “We’re trying to change the scale of making parts from months and years down to days and weeks.”

This article was written by Dan Snetselaar, CNC Product Leader, Protolabs (Maple Plain, MN). For more information, visit here .

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance