Sensor ICs, Semiconductors and Safety

To achieve ISO 26262 compliance, engineering practices must be taken to a higher level. The following insights may prove valuable for getting there.

What system-level risks and related safety implications are lurking within the vehicles you’re developing? Electrification, greater overall electronics content and the trend toward autonomous vehicle operation have engineers concerned that any related failures do not reduce the safety levels already achieved by systems or peripherals.

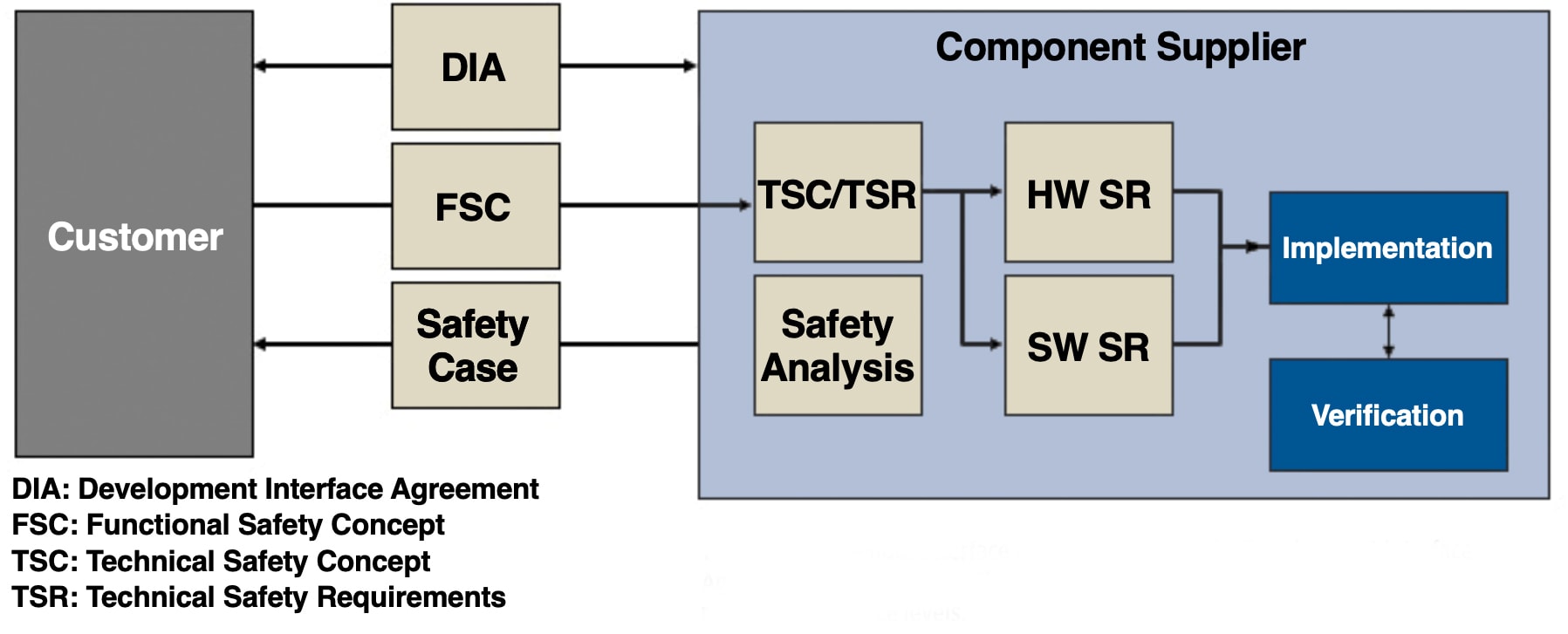

ISO 26262 was created to standardize development processes, to ensure that functional safety is maintained if a vehicle’s electrical and/or electronic systems fail. The goal is to create a safety culture within a company wherein safety is regarded as an integral element in the product development process. The ISO standard also relates to semiconductor products. It requires that a qualification process be applied to the tools (schematic capture, layout, simulation, etc.) utilized to develop integrated circuits (IC.) The compliance of said tools must be verified well before development begins (see figure above).

Any firmware embedded within the IC product must also be developed under safety-compliant processes. The resulting code must be verified for compliance to coding standards — a must for automotive-quality semiconductor products. ISO 26262 influences the customer/vendor relationship by requiring a more structured and defined set of responsibilities for each party. Prior to the standard, it may have been acceptable to maintain a more informal interface between a customer and vendor wherein responsibilities could be loosely defined and flexible.

Standard-IC challenges

To comply with the standard, the customer/vendor interface is now defined through a document known as the Development Interface Agreement (DIA). The DIA specifies the responsibilities assigned to each party at their respective interface levels, including the information required and the work products of the activities to be exchanged; the joint tailoring of the safety life cycle and the appointment of a safety manager on both sides (see graphic above).

An important part of ISO 26262 is the classification of hazard, referred to as the Automotive Safety Integrity Level (ASIL). This is determined through HARA (hazard analysis and risk assessment) normally, by OEMs. For each potential hazard, the probability of exposure, severity and controllability are analyzed before ASIL can be assigned to each safety goal. The standard identifies QM, ASIL A, B, C and D wherein ASIL D is the highest safety level.

For example, designs compliant with ASIL C or D face a much more stringent review process, verification and validation activities, and documentation process relative to designs for levels A and B. As can be expected, elements in the system which are assigned ASIL D will likely have the most comprehensive Technical Safety Concept which provides the mapping between technical safety requirements and architecture elements.

How the technical safety requirements (TSR) flow into a given element’s development process will depend upon where this element exists in the hierarchy of the vehicle development process. For example, the overall safety goals and associated functional safety concept of the vehicle itself are determined at the most initial stages of the vehicle-level concept phase through HARA. Functional safety requirements (FSRs) then flow down to the major subsystems and eventually to individual components. Typically, the further down an element is in the hierarchy, the longer it may take before the FSRs are assigned to the suppliers.

Once the FSRs are assigned, the supplier can then generate the technical safety requirements (TSRs) which will be implemented by the architecture and design of the individual component.

This potential delay in assignment of FSRs can pose a challenge in the development of a complex component such as an IC. The development of an IC product for automotive applications can take several years. However, the FSRs relating to a given IC function may not be well defined until later in the vehicle development process, after the safety requirements have eventually cascaded all the way down to the IC element. In cases where the IC is a custom device (defined specifically for a given purpose in the vehicle), the FSRs are often included in the specification for that specific IC. This makes it somewhat easier for the IC developer to follow the ISO 26262 development process and achieve the assigned safety requirements.

Although custom ICs are often utilized in automotive applications, in many cases a standard product IC may be capable of achieving a given function within the vehicle. The development of the standard IC often starts well before safety requirements are available. Herein resides one of the challenges for automotive-IC developers: how to ensure that a standard IC covers the safety requirements for its target applications.

Cost vs. performance tradeoffs

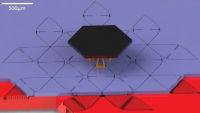

To further complicate matters, a standard IC may find its way into a variety of systems or subsystems within the vehicle. For example, an inductive sensing IC which measures mechanical motion, such as the Microsemi LX3302 (see above graphic), may be utilized for detecting gear movement in a transmission, angular motion detection for steering torque, proximity detection as a brake lamp switch, position detection for electric seat control, and/or a variety of other mechanical motion applications. Although the LX3302 may satisfy each of these applications, the application itself may have different ASIL ratings and safety goals.

As can be expected, the functional safety requirements for the control of an electrically-adjustable seat (ASIL A) will be significantly different than the safety requirements for detecting the torque on a steering wheel (ASIL D).

For a standard product IC, the supplier shoulders the burden of defining the FSRs and writing the TSR for a given product, then implementing safety features and diagnostics which satisfy those TSRs. In such cases, the IC developer treats the IC as a safety element out of context (SEooC). This means the element (in this case the IC) is developed without a specific vehicle, system, subsystem, and/or customer in mind. In other words, the vendor may have several target applications in mind and will then predict the FSR and TSR necessary to address the ASIL level for these applications.

As can be expected, a vendor who is new to the safety requirements of automotive applications may have limited knowledge and/or experience relating to TSRs. As a result, the TSRs generated by this novice vendor may be composed largely of ‘best guess’ requirements. As the vendor gains experience with actual applications, the knowledge base improves and the TSR become more accurate and more comprehensive.

Another challenge faced by the IC developer relates to the trade-offs between the level of diagnostics provided within the IC and the associated impacts to cost and/or performance. The primary goal of ISO 26262 is to ensure that an electronic device does not produce an unsafe behavior, even when a fault occurs within and/or around that device. Given this goal, the IC developer must analyze the IC architecture to determine how IC faults may occur, either through failures within the IC itself or by conditions relating to the environment and/or interfaces around and to the IC.

This can be a complicated analysis, given the number of combinations of conditions which may result in an IC fault or failure. To help constrain this analysis to an achievable level ISO 26262, in most cases, limits the analysis to dual-point fault. In other words, the analysis usually does not need to consider failures which may occur when three (or more) faults occur in parallel.

Implementing safety features

An initial step for the IC developer is to conduct a Failure Modes Effects and Diagnostic Analysis. The FMEDA determines the causes of faults within the IC and the associated effect of that fault on the system. In addition to analyzing the possible faults, the FMEDA identifies the diagnostics implemented to detect these faults. The percentage of faults covered by the diagnostics will be an important indicator to determine if a safety goal violation (due to random hardware failure) is within the requirement of its corresponding ASIL level.

Note that the FMEDA document is a work item which is commonly requested by the customer early in the IC development process.

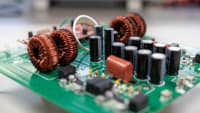

In many cases the diagnostics will take advantage of existing resources within the IC, so the cost impact and/or complexity may be minimal. For example, an IC which already includes an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) may multiplex critical analog signals into this ADC in order to perform diagnostics. In this case the added hardware is limited to the multiplexer switches. In other cases performing a diagnostic may require adding a circuit and/or firmware for which the sole purpose of that circuit (or firmware) is to perform a diagnostic function. This can add cost and increase the complexity of the fault analysis because the new circuit and/or firmware can also fail.

Once the FMEDA is complete and the associated diagnostics are identified, the IC vendor must implement the safety features into the product and verify their effectiveness with traceability back to the top-level safety goal. Safety-centric meetings and audits are conducted throughout the design and verification process in order to achieve this goal.

This verification process, as well as the other added activities required for ISO 26262 compliance, are essentially good engineering practices and disciplines. However, to achieve that compliance these practices are taken to a higher level requiring training, dedicated resources, infrastructure — and a company culture which understands and respects safety as a critical element for automotive component suppliers.

Mark Smith is Product Line Manager, Sensor Products and Luyang Zhang is Systems Applications Engineer, at Microsemi Corp., a manufacturer of semiconductor and system solutions for automotive and other markets.

Top Stories

INSIDERAerospace

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsUnmanned Systems

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

ArticlesUnmanned Systems

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

ArticlesUnmanned Systems

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

Webcasts

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Defense

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Test & Measurement

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Automotive

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility