New Approach Makes Lighter, Safer Lithium-Ion Batteries

Adding polymers and fireproofing to a battery’s current collectors makes it lighter, safer, and about 20% more efficient.

Scientists have re-engineered one of the heaviest battery components — sheets of copper or aluminum foil known as current collectors — so they weigh 80% less and immediately quench any fires that flare up. If adopted, this technology could address two major goals of battery research: extending the driving range of electric vehicles and reducing the danger that laptops, cellphones, and other devices will burst into flames. This is especially important when batteries are charged quickly, creating more of the types of battery damage that can lead to fires.

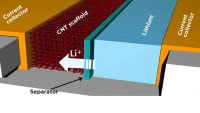

Whether in the form of cylinders or pouches, lithium-ion batteries have two current collectors, one for each electrode. They distribute current flowing in or out of the electrode and account for 15% to as much as 50% of the weight of some high-power or ultrathin batteries.

Shaving a battery’s weight is desirable in itself, enabling lighter devices and reducing the weight of electric vehicles; storing more energy per given weight allows both devices and EVs to go longer between charges. Reducing battery weight and flammability could also have a big impact on recycling by making the transportation of recycled batteries less expensive.

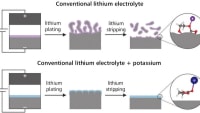

Researchers in the battery industry have been trying to reduce the weight of current collectors by making them thinner or more porous but these attempts have had unwanted side effects — such as making batteries more fragile, chemically unstable, or requiring more electrolyte — that raise the cost.

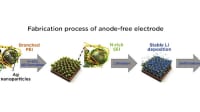

The team designed experiments for making and testing current collectors based on a lightweight polymer called polyimide, which resists fire and stands up to the high temperatures created by fast battery charging. A fire retardant — triphenyl phosphate (TPP) — was embedded in the polymer, which was then coated on both surfaces with an ultrathin layer of copper. The copper would not only do its usual job of distributing current but also protect the polymer and its fire retardant.

Those changes reduced the weight of the current collector by 80% compared to today’s versions, which translates to an energy density increase of 16-26% in various types of batteries and it conducts current just as well as regular collectors with no degradation.

When exposed to an open flame from a lighter, pouch batteries made with today’s commercial current collectors caught fire and burned vigorously until all the electrolyte burned away. But in batteries with the new flame-retardant collectors, the fire never really got going, producing very weak flames that went out within a few seconds and did not flare up again even when the scientists tried to relight it.

One of the big advantages of this approach is that the new collector should be easy to manufacture and also cheaper because it replaces some of the copper with an inexpensive polymer.

For more information, contact Glennda Chui at

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...