Three-Dimensional Plastic Part Extrusion and Conductive Ink Printing for Flexible Electronics

3D printers can be used to print structures with integrated electronics.

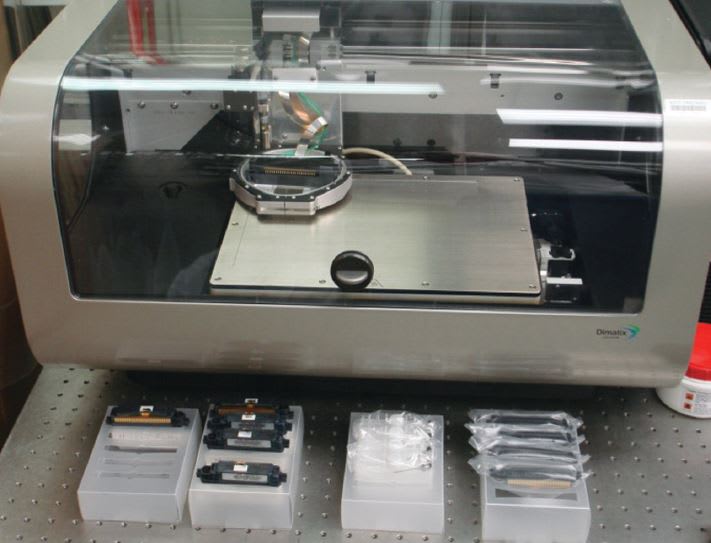

Structural electronics, or structronics, seeks to build wiring and electrical interconnects directly into component structures to diminish the need for structural fasteners. A MakerBot Cupcake Computer Numerical Control (CNC) was used to investigate the fabrication of plastic structures by printing, and a Fujifilm Dimatix Materials Printer (DMP) was used to create flexible Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs). After developing processes to make these machines easier to use, others will be able to utilize them to develop structures with integrated electronics.

The printer works by slicing each model into layers, working from the top of the object to be printed to the bottom of the object to be printed. Then, it uses the layers to generate GCode, a machine code that tells the machine where it needs to deposit plastic on the build platform to print the object layer-bylayer. After generating GCode, the build process can be executed directly from the computer used to slice the model, or by saving the file to a Secure Digital (SD) card, it can be executed with no computer connected to the machine. During the build process, Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) filament is pushed through a nozzle heated to 220 °C in much the same way as a hot glue gun is used to extrude glue. The extruder travels along the path defined by the GCode, leaving behind plastic to build the desired model.

The models used were chosen to investigate four areas of capability with the MakerBot: maximum size of models, minimum feature size of models, hollow object printing, and precision.

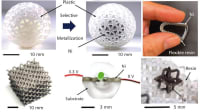

The first test sought to determine the maximum size of a model printed with the MakerBot. The test used a standard 3D printing test print called the Stanford bunny, a model from a repository of 3D scans made by Stanford University that measures 89.42 millimeters tall by 75.95 millimeters wide with a depth of 49.66 millimeters. Height was a limiting factor when printing this model because any attempt to make the object taller than 95 millimeters would be unsuccessful because the extrusion tool would collide with the top of the machine. The width of the object was also on the verge of being too wide for the machine to handle. All of the 3D models are printed on a surface called a raft, which makes objects easier to remove from the printer and serves to prevent failure of an entire print if Z-axis misaligns during printing. While the object size is limited for each print, it is possible to divide objects into several smaller prints and put them together with adhesive or design the parts to snap together.

The second test was to show the minimum feature size achievable on a plastic model made on the MakerBot. The test used a small figure of a NASA space shuttle orbiter that measures 52.45 × 54.48 × 16.11 millimeters. The model shows the minimum feature size attainable on the MakerBot with its three thin wings. The wings measured only 2.57 millimeters at their thickest point, and the smallest of them is only 5.85 millimeters tall.

The third test is the ability to print objects with open spaces in their center. Hollow objects are difficult with 3D printers because of the nature of an additive building process. It is impossible to deposit melted plastic into the air and have it stay in place, but objects can be made that are hollow given proper planning. One model that shows this is the hollow pyramid model that measures 36.78 × 36.74 × 32.65 mm. By making the sides less than a 45-degree angle, the overhangs made by the printer assures that the upper parts of the model do not fall, which makes it possible to print models with open spaces.

The fourth capability of the MakerBot to be tested is precision printing. With the MakerBot, a product can be created that is broken down into several smaller parts for easier printing or to allow for moving parts, such as hinged arms. Two designs of very similar models were created to test this capability. The iris box model is a cylindrical box designed to open by twisting the top of the box, which should allow the shutters that seal the box to rotate outwards and reveal the contents of the box. While the MakerBot is unable to print small objects like pegs that fit exactly where they are supposed to fit, it is capable of printing parts that fit together.

With more testing, the integration of electronics into structural components is achievable with the current equipment. The MakerBot Cupcake CNC can print prototypes, as long as they are designed such that no single print is larger than the area the extruder can travel. Metallic traces deposited on substrates by the Dimatix printer are viable for use as flexible PCBs, and could be used to make a circuit board that goes around or inside of a prototype printed on the MakerBot.

This work was done by Tracy D. Hudson and Carrie D. Hill of the Army Research, Development, and Engineering Command. ARL-0148

This Brief includes a Technical Support Package (TSP).

Three-Dimensional Plastic Part Extrusion and Conductive Ink Printing for Flexible Electronics

(reference ARL-0148) is currently available for download from the TSP library.

Don't have an account?

Overview

The Technical Report RDMR-WS-12-04, authored by Tracy D. Hudson and Carrie D. Hill from the Weapons Sciences Directorate, focuses on advancements in three-dimensional (3D) plastic part extrusion and conductive ink printing, specifically for flexible electronics. Published in April 2012, the report is intended for public release and aims to provide insights into innovative manufacturing techniques that can enhance the production of flexible electronic devices.

The report begins by outlining the significance of 3D printing technology in the context of manufacturing, particularly for creating complex geometries that traditional methods may not easily achieve. It emphasizes the potential of 3D plastic part extrusion to produce lightweight, durable components that can be tailored to specific applications in various industries, including defense and aerospace.

A key aspect of the report is its exploration of conductive ink printing, which allows for the integration of electronic functionalities into flexible substrates. This technology is crucial for developing next-generation electronic devices that require flexibility and adaptability, such as wearable electronics and smart textiles. The authors discuss the materials used in conductive inks, their properties, and the challenges associated with ensuring reliable conductivity in printed circuits.

The report also addresses the estimated time required for printing processes, providing a practical perspective on the efficiency and scalability of these technologies. It highlights the importance of optimizing printing parameters to achieve high-quality outputs while minimizing production time and costs.

Furthermore, the document includes a disclaimer stating that the findings and views expressed do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense. It clarifies that references to specific commercial products or processes do not imply endorsement or approval by the U.S. government.

In conclusion, the report serves as a comprehensive resource for understanding the current state and future potential of 3D plastic part extrusion and conductive ink printing in flexible electronics. It underscores the transformative impact these technologies can have on manufacturing processes, paving the way for innovative applications in various fields. The findings aim to inspire further research and development in this rapidly evolving area of technology.

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance