Are We Stuck with Lithium-Ion?

As companies continue to trumpet their next-gen EV battery tech, it seems like new chemistries face more momentum from the established champ, lithium-ion.

There’s no shortage of alternatives to lithium-ion EV batteries in development. From lithium-iron phosphate to sodium-ion to multiple solid-state chemistries, companies are racing to perfect these technologies and figure out how to manufacture them at scale. But to an outside observer, it can feel like breathless coverage of future battery technology is much ado about not much. Lithium-ion batteries seem to have all the momentum, seeing as they’re the power supply of choice for most EV manufacturers. And if there’s anything that’s true in the automotive industry, it’s how hard it is to buck momentum. Here are just a few of the big issues lithium-ion batteries have in their favor:

- Already built factories that manufacture batteries and face tremendous costs to retool for a different technology.

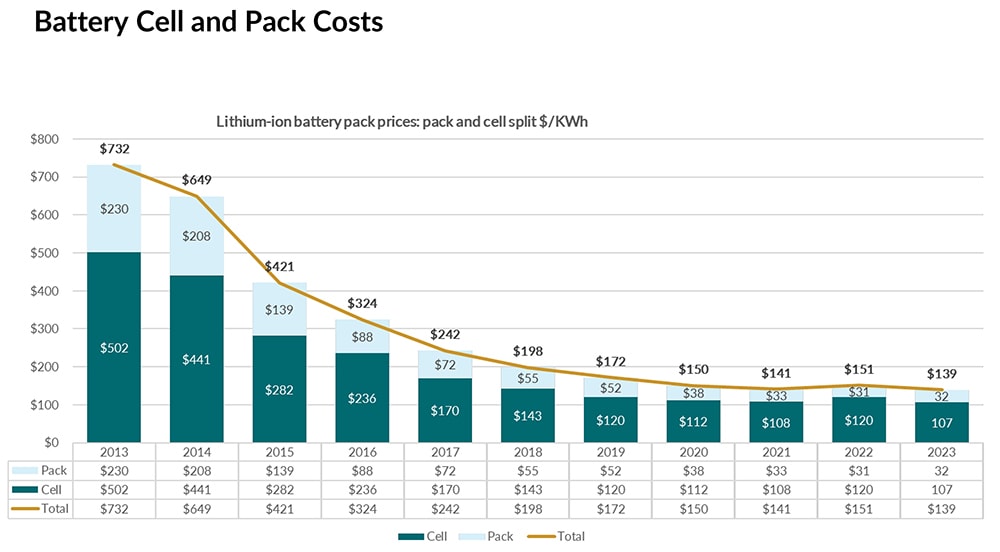

- An economy of scale that has driven down the cost per kilowatt-hour from $732 in 2013 to $139 in 2023.

- The vehicle development curve can be seven or more years before hitting production. That means betting on a technology and a mining and manufacturing ecosystem that hasn’t been fully tested.

- Some companies are slowing EV launches and reconsidering investment in new technologies given the recent slowdown in the growth of EV sales.

At the same time, it’s strategically important to the industry to diversify its power sources, as China effectively controls the lithium-ion battery market.

Keith Norman, chief sustainability officer for battery maker Lyten, said that the same lithium-ion momentum in the mobility industry is also being experienced by the home and industrial-energy-storage industry (such as Tesla’s Powerwall). Norman said lithium-ion chemistry is probably not the ideal solution for either, but it’s the easiest for now. “When you get a solution like lithium-ion that meets the market demands for tolerances that you have to show to play in the space, you can grow very, very rapidly,” Norman said. “Our view is that you're going to see something a little bit similar [in alternate chemistries]. There probably won’t be tens of chemistries. It’s going to be a small number that will find their place and grow very rapidly.”

Lyten’s Li-S ramp

While Lyten is all-in on lithium-sulfur chemistry due in large part to the fact that sulfur is one of the most widely available and lowest-cost minerals available, it is another material that sets the company’s batteries apart. “The real innovation is a new material, a three-dimensional graphene material that is ultra-high-strength and high conductivity that allows us to tune structural and permeability properties … to go deliver performance gains in industrial products,” Norman said. Like some companies in the e-motor business, Lyten is focusing on other applications, such as drones, satellites and other defense applications before homing in on mobility. The biggest challenge on the table is increasing the rechargeability of the cells, which the company is already producing in San Jose, California.

Compared to today's most common lithium-ion chemistries, Norman said Lyten, with its Li-S battery, is nearing an energy density of 20% to 25% above NMC batteries and has a target of two times that of NMC in the longer term. The other calling card of Lyten’s batteries: a lack of weight, which, in addition to energy density, is another way to extend an EV’s range. And what may attract attention is a claimed 50% reduction in cost versus lithium-ion batteries.

So far, Norman said, Lyten can manufacture cells using the same equipment currently on most lithium-ion manufacturing lines. That’s important. Dan Lee, a senior manager at Plante and Moran in Michigan, said the investment in today’s gigafactories is just too big to be easily written off. “When you look at OEMs investing, you know, $2 billion or $3 billion, at least, on gigafactories, that’s a big ask that five years down the line, all your capital equipment is worthless,” Lee said.

He also said that some OEMs and suppliers still believe there’s efficiency still to be wrung out of lithium-ion technology, adding another incentive to stick with current technology. “Tesla's still dialing it in. It has been able to alter the cathode process where they're using a dry cathode process in the Austin gigafactory,” he said. They’ve removed some of the curing time. It’s all about how you simplify the manufacturing process” to take time out of it, he said.

Wide range of predictions on “when”

Despite the clear hurdles, most independent analysts agree that new battery technology will come to the market. The question is when. Most estimates range anywhere from five to 15 years. As for who is most likely to step forward first, Plante and Moran’s Lee suspects it will come from a non-OEM startup or supplier. “It could be Tesla or BYD, companies with a strong core competency in battery manufacturing. [The OEMs’] internal capabilities to develop a new chemistry in the lab and bring it to production, I think, are lacking,” he said. “That's why you see OEMs, via their venture capital arms, making investments into some of these technologies.

Siyu Huang, founder and CEO of Factorial Energy, which is betting on its quasi solid-state technology, said the race to get to market is fierce. “Everybody’s looking at a timeline from ’26, ’27, ’28 or ’29, around that time frame,” he said. “We are very committed to bringing the technology to the market the soonest among all of the players.”

Factorial’s solid-state tech

Factorial Energy uses a polymer-based solid-state electrolyte system. The use of a polymer either results in low energy density or no improvement in weight, both of which affect range. “We developed a polymer-based solid-state technology that also uses some liquid in the system, and by having a liquid there,” Huang said, “we’ll be able to utilize more than 80% of the manufacturing process for today’s lithium-ion manufacturing.”

She also said they are targeting up to 50% higher energy density and 50% weight reduction also. “Traditional lithium-ion battery EVs are about 1,000 to 3,000 pounds heavier than traditional combustion-engine vehicles. If we’re able to produce a battery that’s even 30% lighter than today’s lithium-ion battery, that’s about 100 kg or 200 pounds.”

Solid-state technologies tend to be more thermally stable, so more weight reduction could come with the deletion of thermal-management equipment, Huang said. Managing investment, managing expectations

Plante Moran’s Lee and Lyten’s Norman said it would take continued government investment in the industry to bring new technologies such as these to the automotive market. Lee said the Inflation Reduction Act and the bipartisan infrastructure law have $7 billion earmarked for battery materials and manufacturing research. But it will still take plenty of private investment to spool up future battery tech.

George Cuff, director of automotive for the manufacturing intelligence company Hexagon, said that despite the headwinds, he sees battery production in the United States growing year after year. “Some of that expansion is being tempered because of the overall market with electric vehicles, but I do expect long-term that the overall battery production in North America will continue to rise year over year,” he said. “It just may be later than what was originally announced by the OEMs and their battery manufacturing suppliers like LG Chem and the other battery suppliers out there.”

Norman had a word of caution for the many companies clamoring to get the attention of media and investors as they explore the innovations that experts insist will make their way into vehicles. “The battery industry has not done itself a lot of favors” by getting giddy about technologies that can’t yet be scaled,” he said.

Top Stories

NewsSensors/Data Acquisition

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERWeapons Systems

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

NewsAutomotive

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

INSIDERAerospace

![]() Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

Active Strake System Cuts Cruise Drag, Boosts Flight Efficiency

ArticlesTransportation

Webcasts

Aerospace

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Energy

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance