Seeing Through Fog

Fog, rain and snow are big challenges for optical sensors, particularly active systems. Engineers need to understand the impact of fog conditions on cameras and thermal sensors used in AVs.

As the mobility industry advances with ADAS and autonomous vehicle (AV) operation, the safety challenges of applications involving nighttime warning systems, pedestrian detection and driver situational awareness will surely warrant redundant systems. Thermal sensors will continue to be an important component of the sensor suite that makes safe autonomy a reality.

Although the value of thermal sensors is widely acknowledged for nighttime driving, a key issue that has limited their full-scale adoption has been cost. It is important to note that infrared imaging sensors are semiconductors, so the same economics of scale apply to infrared sensors as apply to other silicon-chip products. The costs for high resolution thermal sensors are projected to decline to well under $250 with their large scale adoption in ADAS systems.

As the price enables developers to include thermal sensors, it is important to identify why they are needed and where they complement the ADAS sensor suite to make roads safer.

Delivering high-quality data and images to the ‘brains’ of autonomous vehicles in low light and under poor driving conditions is a major challenge for ADAS developers. Fog, rain and snow are big challenges for optical sensors, particularly active systems. Engineers need to understand the interaction of light energy across the visible and infrared spectrum with water vapor — specifically, the impact of fog conditions on optical systems such as visible cameras and thermal sensors.

Modeling with MODTRAN

Fog is a visible aggregate of minute water droplets suspended in the atmosphere at or near the surface of the earth. When air is almost saturated with water vapor, the relative humidity is close to 100% and fog can form in the presence of a sufficient number of condensation nuclei, which can be smoke or dust particles.

There are different types of fog. Advection fog is formed through the mixing of two air masses with different temperatures and/or humidity. Radiative fog is formed in a process of radiative cooling of the air at temperatures close to the dew point. Some fogbanks are denser than others because the water droplets have grown bigger through accretion. The question whether scattering is less in the IR waveband compared to the visible range depends on the size distribution of the droplets.

MODTRAN is used to model the atmosphere under a variety of atmospheric conditions. Developed by the U.S. Air Force, it can predict atmospheric properties including path radiances, path transmission, sky radiances and surface reaching solar and lunar irradiances for a wide range of wavelengths and spectral resolutions. MODTRAN offers six climate models for different geographical latitudes and seasons.

The model also defines six different aerosol types which can appear in each of the climates. Each of the climate models can be combined with the different aerosols. The distance an optical sensor can see will also depend on the climate and the type of aerosol which is present in this specific climate.

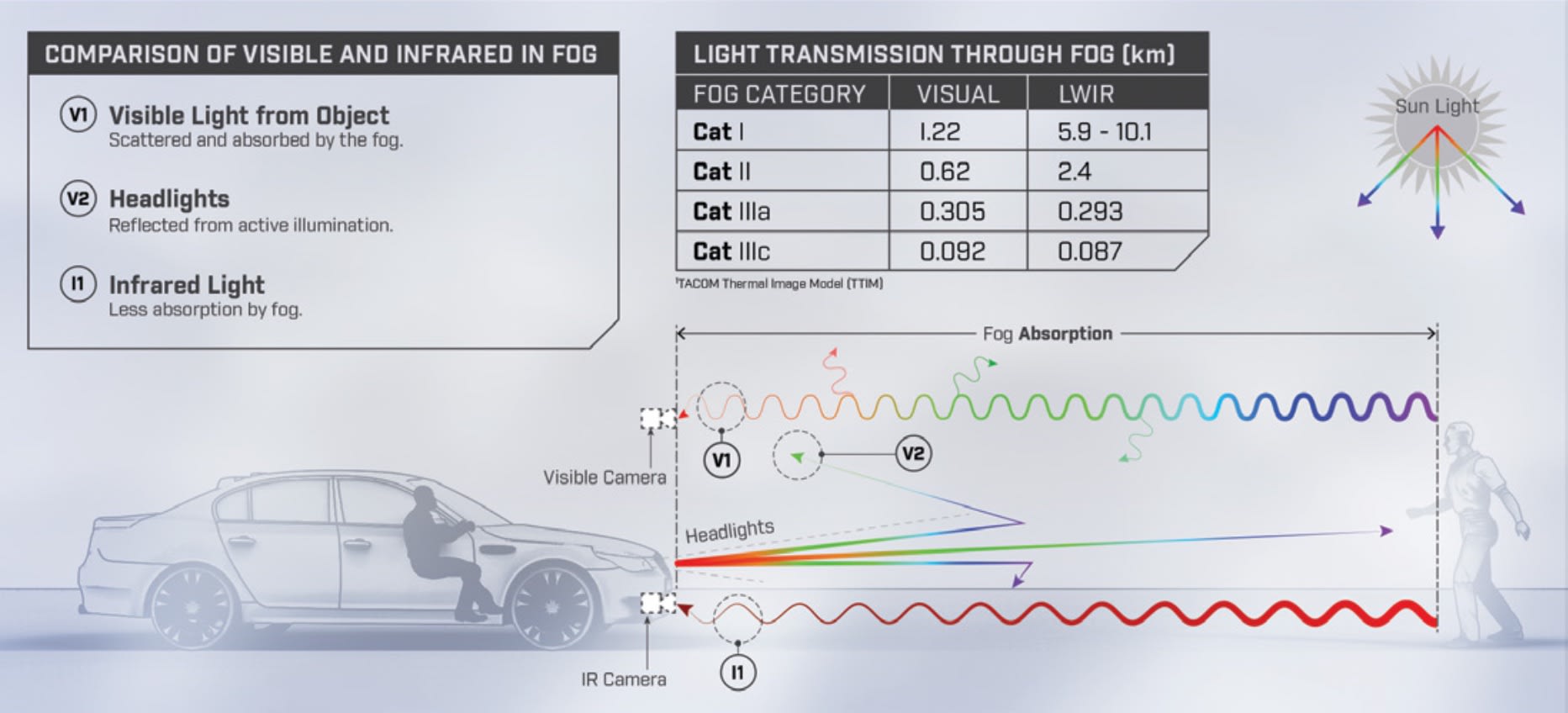

The spectral transmission of the atmosphere for varying ranges enables a simple qualitative comparison of the visible (0.4 to 0.75 microns) and thermal (8 to 12 microns) transmission in different atmospheric conditions and fog type. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) classifies fog in four categories:

- Category I: In fog in mid-latitude summer and rural aerosols, the visible spectral waveband demonstrates significantly lower transmission than in thermal IR wavelengths.

- Category II: Radiative fog is used in this category and the model predicts that transmission in the thermal band is superior to the visible band.

- Category IIIa and Category IIIc: The model states that transmission in the visible and thermal wavelengths are essentially equivalent.

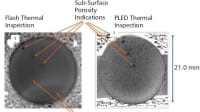

The model compares the detection range in kilometers through fog with the naked eye and an LWIR camera, given a temperature difference of 10°C between the target and the background and a detection threshold of 0.15 K. The graphic on p. 17 includes the qualitative results of the model.

The model and data provide transmission performance, which is driven by several factors. The reason for degradation of visibility in a foggy atmosphere is the absorption, reflection and scattering of illumination by water aerosols. All drivers have experienced driving in heavy fog and poor visibility when using headlights. The light photons from headlights immediately begins to scatter and reflect.

The limited light, if any at night, coming from the driving scene is absorbed and scattered, so the main visible photons the visible camera collects are of the fog itself.

While thermal light photons exhibit the same basic characteristics as visible light, the thermal energy is emitted by the surroundings so the path the thermal light energy takes between an object and the camera takes only one pass. There are loses due to scatter and reflection, but in most fog conditions the transmission is higher in the thermal bands than in the visible spectrum, so the losses are much lower.

Thermal imaging, Machine learning

The addition of thermal sensors to the ADAS sensor suite will clearly increase safety on the road. Thermal sensors see in darkness and challenging lighting conditions such as fog. As the photos on p. 16 illustrate, a vision-based autonomous system will simply become blind in a frequently experienced driving condition. They can detect and classify objects in a cluttered environment. The next challenge is to integrate thermal sensors into the fused detection and classification algorithms.

An additional promising area for thermal sensors, beyond seeing at night and through poor visibility situations, is semantic segmentation or dense labeling, a deep learning technique that describes the process of associating each pixel of an image with a class label (structure, person, road marker, animal, road or car). Initial results demonstrated by FLIR Systems, which has delivered more than 500,000 longwave infrared (LWIR) thermal cameras to date, indicate that thermal images can produce accurate classifications of most of the object classes of interest.

The ability to classify complex automotive driving scenes quickly and accurately using thermal imagery is a key part of increasing safety of ADAS and future autonomous vehicles. While open-source visible light training data sets exist, publicly-available thermal image training data sets do not, making the initial evaluation of thermal imaging more challenging. An annotated training data set from FLIR will create the opportunity for developers to more quickly test and integrate thermal sensors into their ADAS sensor suites.

Thermal cameras are and will become even more affordable with additional manufacturing scale. They deliver high resolution data and fill significant sensor gaps that exist in current ADAS approaches, especially in challenging lighting conditions.

Top Stories

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERAerospace

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsUnmanned Systems

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

NewsDesign

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Connectivity

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable Vehicles

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable Vehicles

Manufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation