Growing Natural Tire Rubber in North America

Despite ongoing advances in polymer chemistry and biochemistry, natural rubber made from rubber trees continues to be crucial to the global tire industry. This is because synthetic rubber often cannot sit-in as a substitute for the natural version.

“For relatively light-duty passenger car tires, 60% to 80% synthetic rubber content is fine, but for heavy-duty commercial truck and off-road tires you need greater durability, so makers typically use from 60% to 80% natural rubber in them,” said Chuck Yurkovich, Senior Vice President of Global R&D at Cooper Tire & Rubber.

It may seem surprising that tire rubber is often best made old-school, from milky latex that is tapped from rubber trees very much like maple tree sap is collected to make maple syrup. For around 125 years, car and truck tires have been made using natural rubber from tropical rubber trees, a species that botanists call Hevea brasiliensis. But more than 80% of Hevea tree farming is concentrated in the South Asian nations of Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, and Vietnam, a fact that has long sparked concerns about business risks stemming from potential geopolitical problems, climate change, and supply-price instabilities, said Bill Niaura, Bridgestone Americas’ Director of New Business Development. Apprehension also arises because Hevea cultivation relies on monoculture forests of identical, cloned trees that are all susceptible to the same diseases and pests.

“Natural rubber is Bridgestone’s single largest raw material purchase, accounting for more than 25%,” Niaura said. “It’s a market-based commodity that has a huge impact on profitability in a low-margin business. Right now, we’re essentially single-sourced. We want to diversify both biologically and geographically.”

These priorities have led several tire makers, notably Bridgestone and Cooper Tire, to pursue development of a practical and economic domestic alternative to rubber trees—the guayule plant (pronounced “gwah-yoo-lee”), a flowering woody shrub that is native to the Sonoran Desert of the Southwestern U.S. and Mexico. After a couple of years working on this alternative source for natural rubber, these efforts are starting to show results. Pilot production has begun and sample tires have been built and tested with promising results, raising hopes that guayule crop production and tire manufacture might start within a decade or so.

“In the last 5 or 10 years the technology has improved to the point of technical feasibility, enough to seem that it could be made to work economically in a reasonable amount of time,” Yurkovich noted. “Our goal is for the yield per acre of guayule to equal that of Hevea trees.”

Growing guayule

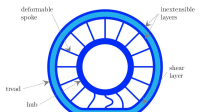

Like Hevea rubber trees, guayule plants contain natural rubber—known to chemists as isoprene, the elastomeric polymer that not only gives tires their bounce, but also their strength, toughness, and load-bearing ability. Unlike rubber trees, in which the isoprene is contained in the latex, guayule’s rubber lies in a layer of cells just below the bark that must be mechanically crushed to extract it.

Guayule rubber, in addition, contains its own set of gels, proteins, and enzymes, which poses different processing and application issues from those associated with Hevea rubber. For example, antioxidants need to be added to the raw guayule rubber to maintain chemical stability. Finally, guayule plants have never been grown on a truly industrial scale.

By no means is guayule rubber new, however. Pre-Columbian peoples used it to make game balls, and the 20th Century saw several companies produce first wild and later cultivated guayule rubber. During World War II the U.S. government investigated guayule and in the 1980s Firestone (now Bridgestone Americas) teamed up with the Department of Defense and the Gila River Indian Community to do so.

In fact, the biggest problem for guayule has been its unsuccessful history of commercial development, said Mike Fraley, Chief Executive Officer of PanAridus, a small agro-tech firm in Casa Grande, AZ. PanAridus is collaborating with Cooper Tire and others in a Biomass Research Development Initiative, a five-year, $6.9-million research program funded by the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Energy to develop a domestic source of natural rubber.

“We want to make guayule economically feasible all the way from the growing through the processing and on to end use,” Fraley said. “Ultimately, we want to make it a drop-in replacement for Hevea rubber.”

Bettering the breed

PanAridus has supplied the consortium with several thousand pounds of guayule rubber while working to maximize crop yields and better the extraction process. “There’s been a lack of advancement in guayule genetics,” Fraley said. “We’re using conventional breeding methods to isolate the plant characteristics that we’re looking for and propagate them.”

“The guayule germ plasm of the World War II-era had a yield of about 1250 lb/acre of rubber,” Fraley said. “We’re now close to 2000 lb/acre.”

In the past, he continued, young plants had to be transplanted from greenhouses, which is time-consuming and less suitable for large-scale crop production than planting seeds.

“PanAridus has developed a direct seeding method, which is what farmers want. We’re also working to ‘annualize’ guayule, which is a perennial,” he said.

Other consortium partners are tackling related issues. A group at Arizona State University studies life-cycle costs, while a Cornell University team develops molecular breeding tools and specialists at the Agricultural Research Service of the USDA work on agronomics and irrigation methods.

Bridgestone’s in-house R&D

Bridgestone has meanwhile established a rather extensive in-house effort to commercialize guayule. Starting in 2011, it began building a 281-acre (114-ha) Agro Operation Guayule Research Farm in Eloy, AZ, to supply samples of dry guayule for experimentation. The farm facility is also trying to optimize crop yields and develop best farming methods while working to strengthen relations with local independent growers. At the company’s Biorubber Process Research Center in Mesa, AZ, 30 researchers and technicians work to perfect the processing route.

“Large-scale production of bales of dry rubber at lowest net cost is our goal, but it requires a fairly capital-intensive operation,” Niaura said. “Unlike Hevea, with guayule you harvest the entire shrub, which grows in two or three years. Only a minority fraction, maybe 5% by weight, is rubber. About 5% is resin that must be removed and the remaining residue—the woody plant parts—has to be meaningfully monetized.”

First technicians grind and mill the harvested plants into uniform particle sizes, then they crush the pulp. “Next, the rubber and resin are dissolved using a mixture of polar and non-polar solvents,” he said. The resulting liquid is dried to remove the solvents and separated. The resin has industrial applications as does the solid residue, which can be used in biomass operations to make fuel or power. “If you do it right, there’s no waste.”

Both Bridgestone and Cooper Tire reported that they have completed several guayule-based tire builds and sent them to customers for road testing. Converting to guayule rubber means “reformulating each component of the tire individually,” Yurkovich said. “Then you test them to develop confidence. We’re seeing good levels of performance, at least equal to those of current tires.”

Top Stories

NewsRF & Microwave Electronics

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

INSIDERAerospace

![]() A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

A Next Generation Helmet System for Navy Pilots

INSIDERDesign

![]() New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

New Raytheon and Lockheed Martin Agreements Expand Missile Defense Production

INSIDERMaterials

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

NewsPower

![]() Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

Ford Announces 48-Volt Architecture for Future Electric Truck

ArticlesAR/AI

Webcasts

Electronics & Computers

![]() Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Cooling a New Generation of Aerospace and Defense Embedded...

Automotive

![]() Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Battery Abuse Testing: Pushing to Failure

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design Cycle

Automotive

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive &...

Energy

![]() Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance

Sesame Solar's Nanogrid Tech Promises Major Gains in Drone Endurance