Nanoparticle Networking Could Lead to Fast-Charging Batteries

A new electrode design for lithium-ion batteries has been shown to potentially reduce the charging time from hours to minutes by replacing the conventional graphite electrode with a network of tin-oxide nanoparticles.

Batteries have two electrodes, an anode and a cathode. The anodes in most of today's lithium-ion batteries are made of graphite.

The theoretical maximum storage capacity of graphite is very limited, at 372 mA·h/g, hindering significant advances in battery technology, according to Vilas Pol, Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering at Purdue University.

Researchers have performed experiments with a "porous interconnected" tin-oxide based anode, which has nearly twice the theoretical charging capacity of graphite. The researchers demonstrated that the experimental anode can be charged in 30 minutes and still have a capacity of 430 mA·h/g, which is greater than the theoretical maximum capacity for graphite when charged slowly over 10 hours.

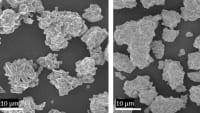

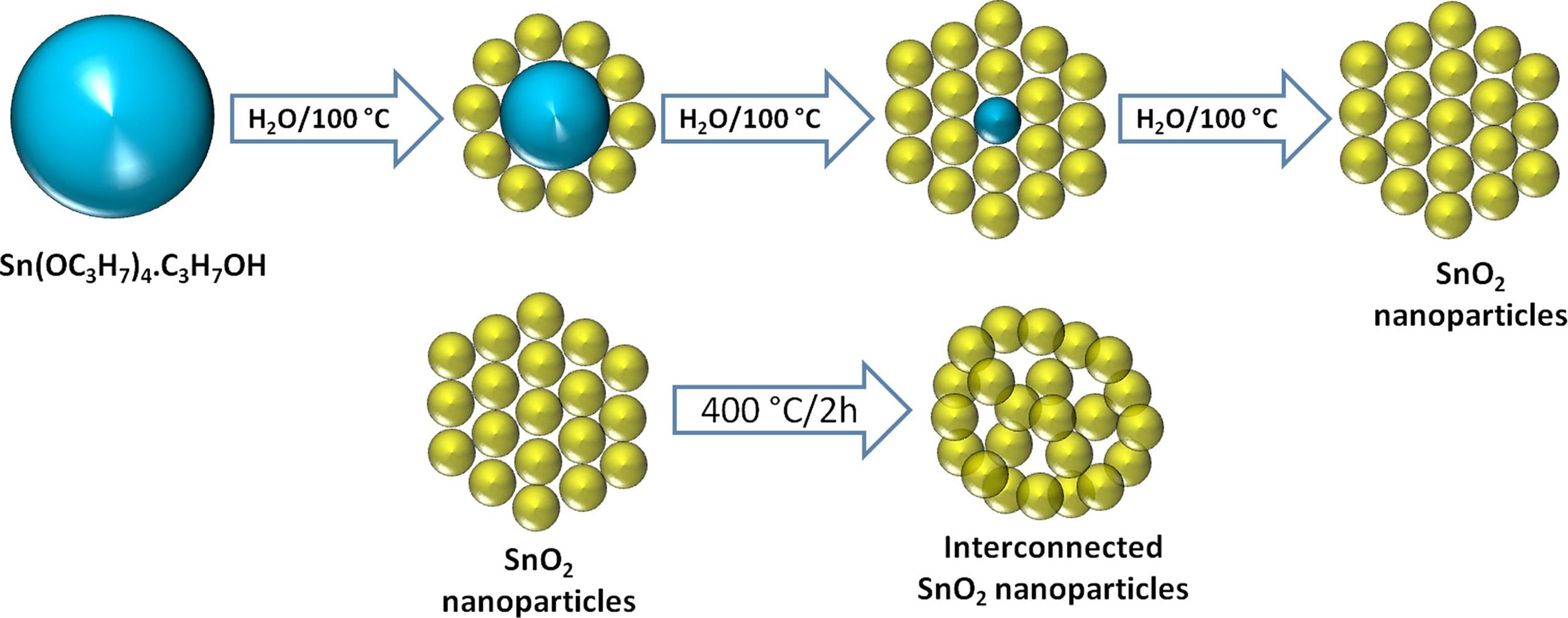

The anode consists of an "ordered network" of interconnected tin oxide nanoparticles that would be practical for commercial manufacture because they are synthesized by adding the tin alkoxide precursor into boiling water followed by heat treatment, Pol said.

"We are not using any sophisticated chemistry here," Pol said. "This is very straightforward rapid 'cooking' of a metal-organic precursor in boiling water. The precursor compound is a solid tin alkoxide—a material analogous to cost-efficient and broadly available titanium alkoxides. It will certainly become fully affordable in the perspective of broad-scale applications."

When tin oxide nanoparticles are heated at 400°C they self-assemble into a network containing pores that allow the material to expand and contract, or breathe, during the charge-discharge battery cycle.

"These spaces are very important for this architecture," said Purdue postdoctoral research associate Vinodkumar Etacheri. "Without the proper pore size, and interconnection between individual tin oxide nanoparticles, the battery fails."

The researchers included Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences researchers Gulaim A. Seisenbaeva, Geoffrey Daniel, and Vadim G. Kessler; James Caruthers, Purdue's Gerald and Sarah Skidmore Professor of Chemical Engineering; Jeàn-Marie Nedelec, a researcher from Clermont Université in France; and Pol and Etacheri.

Electron microscopy studies were performed at the Birck Nanotechnology Center in Purdue's Discovery Park. Future research will include work to test the battery's ability to operate over many charge-discharge cycles in fully functioning batteries

Top Stories

INSIDERManufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsTransportation

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

EditorialDesign

![]() DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

DarkSky One Wants to Make the World a Darker Place

INSIDERMaterials

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Defense

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

Automotive

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable...

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Electronics & Computers

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Unmanned Systems

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...