Designs to Dye for: Autonomy’s New-Materials Revolution

From pineapples to bacteria, Envisage’s research is focused on new mobility’s ‘inside’ story.

Evolving vehicle engineering constantly reshapes vehicle architectures. But along with electrified drive-trains and autonomous capabilities is the need for a mindset shift in materials, opening the way for new sustainable solutions in color, materials and finish (CMF). Future cabins could have pineapple, banana, coconut and eucalyptus among the material solutions — with bacteria playing a potentially positive role.

All these sources are at play for research designer Sammie Mayers-Nissen and her colleagues at Envisage, the U.K.-based specialist engineering services provider helping to find sustainable alternatives to plastic, leather and harmful dyes that still meet quality, durability and cost demands. “As always, in terms of R&D of alternative materials and color, production-cost consideration is the massive driver, with performance very close behind,” said Mayers-Nissen.

Key differentiator

In the decades ahead, sustainable solutions for CMF are likely to be key differentiators between products increasingly becoming like today’s white goods—an emerging customer “need” neglected by the industry, warned Envisage’s engineering director, Paul Arkesden. “OEMs spending hundreds of millions of dollars on major electrification and autonomous-systems programs have very little extra time or money themselves to invest in new product materials and finishes,” Arkesden contends. “That crucial niche is in sharp focus for Sammie and her team with their specific knowledge. And our moral compass is driving us down routes ahead of legislation.”

This is why Envisage is looking at so many material sources, not just those already tested and qualified for automotive use. They’re referencing other industrial sectors with potential for extrapolation to various vehicle interior finish and substrate applications. “What must be realized is that sustainability is not one dimensional,” stressed Mayers-Nissen. “The many aspects to be considered include water usage, petroleum consumption, electricity demands and traceability – its physical journey and its narrative for the customer.”

“In the case of wool, right down to the farm and individual sheep. There is now a wish by consumers to consider such things, particularly plastic alternatives,” Mayers-Nissen explained. “Many industries have adopted more sustainable processes in both composition and manufacturing of materials, so Envisage is exploring their realistic application in future vehicles while highlighting areas for further investigation.”

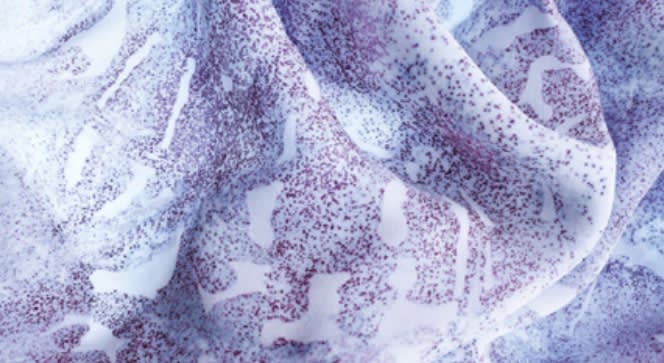

Color-fastness is a crucial automotive test, but many sustainable materials and dyes fail this test, for example as an airbag cover or trim stitching subject to UV effect. Bacterially-derived pigments offer sustainable solutions to avoid harmful dye processes, but coloring changes over time prevent automaker consideration. For autonomous or on-demand vehicles – providing it fades in a consistent way – this shouldn’t be an issue, as the customer might never again see that particular vehicle.

Reviewing CMF testing

Mayers-Nissen and Arkesden stressed that in light of the huge changes the automotive industry is undergoing, reviewing its CMF test legislation would help material suppliers expand the range of sustainable materials. This is where pineapple, coconut and other plant or tree sources enter the picture. “No, your car would not smell like a crate of pineapples on a hot day,” insisted Mayers-Nissen, but scents for materials do represent part of the R&D work.

A former head of engineering at McLaren Special Operations and program manager for the McLaren P1 hypercar, Arkesden is fully aware of the need to ensure the effective transition from laboratory to the production line. He notes they must of course meet all safety, durability, efficiency and aesthetic requirements, “and at the rate of a million or more units per annum. Fortunately, engineers do love a challenge!”

The materials

A review by Mayers-Nissen of potential sustainable CMF solutions:

Leather alternatives

PBN Associates: Chimera engineered leather is created by infusing collagen (as used in face creams) sourced from the raw hide (and free of any tannery chemicals) into an ultra-fine mat of polyamide microfibers. Its use in manufacturing results in a 25% energy savings compared to existing microfiber leather and 55% less than producing genuine leather.

Malai Biomaterials Design: The company works with processing plants in India to collect waste coconut water to feed bacterial cellulose production. Enriched with plant-based materials such as banana and coconut fibers, it is dried and finished to create Malai, which is comparable in texture to leather but without the toxic tempering processes. Not putting the recycled coconut water back into the soil reduces acidification detrimental for crop growth. Although not yet regarded as suitable for automotive applications, it is another alternative material for OEM and supplier awareness.

Natural-fiber substrates

Bcomp: Natural flax fibers enable innovative composite material solutions. Use is made by this Swiss company of a lightweight, high-performance natural-fiber composite-reinforcement grid. It could be used as a substrate to replace or reinforce automotive carbon fiber, with benefits including lower cost, weight and environmental impact. Volvo has used it in an XC60 demonstrator for recycled plastics use. Bcomp’s focus also encompasses motorsport, including GT Electric.

Kenaf (material): A substitute for petroleum-based plastics, it is a bast fiber (a plant’s fibrous material; in this case extracted from the mallow plant), which converts an above-average volume of CO2 to oxygen as it grows. Benefits include weight saving; BMW has used it in the electric i3. Mercedes-Benz has used it in the E-Class as “FiberFrame” developed by International Automotive Components, saving a claimed 50% in weight compared to a conventional metal-reinforced sunroof frame.

Textile and unusual fibers

Ananas Anam: Piñatex is a natural textile made from pineapple leaf fiber, with the leaves a byproduct of existing agriculture. It has low environmental impact/high social responsibility and markets include automotive interior trim. Manufacture involves the long fibers of the plant’s leaves being extracted via a process called decortification.

When the leaves have been stripped, the waste biomass has further uses, including biofuel. The fibers are de-gummed and undergo an industrial process to become a non-woven mesh to form the base of Piñatex, which is then sent to Spain for specialized finishing, creating a leather-like appearance designed to be soft and flexible, but durable. The floor mats of Skoda’s Vision RS concept seen at last year’s Paris Motor Show use Piñatex.

Camira Fabrics: Camira blends bast from nettles, hemp and flax collected from the inner “bark” that surround the stem with pure new wool. Bast fiber material is currently used in commercial areas but has not been tested to automotive standards. However, their Rivet range uses Repreve polyester made from recycled plastic bottles. Repreve material has been used by BMW and Ford.

Paper and cork

Richlite: Richlite (company and product name) is described as a durable, versatile, highly-sustainable material made from resin-infused paper. Originally developed in the 1940s for industrial tooling and pattern making, it now is used as a premium surface material for application in automotive, aerospace and other industries. It comprises approximately 65% FSC (the international Forest Stewardship Council) - certified recycled paper content and 35% phenolic resin. It could be considered not just for automotive tooling but for its aesthetic appeal in a car.

JPS Cork Group: Its cork products are renewable and sustainable. The removal of the ‘cork’ bark does not harm the tree and is harvested on average every nine years. It is easily machinable. JPS Cork has developed its cork fabric using a cotton or polyester backing to enable easier use. It could make unique automotive flooring when machined. When backed on fabric, it is easily trimmed on a door card or dashboard.

Social sustainability

Lenzing Group: The Austrian company produces a range of fabrics using wood-pulp cellulose. Viscose and rayon are made from wood cellulose. The material is not new; it’s the sustainable production methods used that set it apart. The company’s Lycell technology/ material requires only a third of the water needed in viscose technology and its Modal material doesn’t require as much water as a regular dyeing process due to the fibers’ absorbent quality. Its Tencel product is a form of rayon that uses cellulose fiber made from wood pulp.

Dyes and pigments

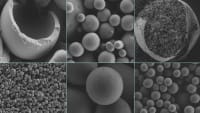

Faber Futures: In London, Natsai Audrey Chieza, designer and founder of Faber Futures, an R&D studio creating biologically inspired materials, creates textiles that are dyed using bacteria with no chemical fixatives. For example, a small amount of pigment-producing bacteria developed over 34 days results in vivid pinks, blues, greens and yellows. Because it is a living pigment, little or no water is required in the application process. Removed from the lab, the bacteria die, but the pigment stays on the textile.

We aRe SpinDye: This Swedish company is revolutionizing the dyeing process with sustainability and environmental protection a priority. Color pigments are added to recycled plastic pellets, melted down and added to SpinDye undyed material and yarn. The result is 75% less water and 90% fewer chemicals are used in the process, and the company states that there is 100% color consistency between finishes and fabrics. The process has only been developed with chemical fibers such as polyester, polyamide, polypropylene and viscos (semi-synthetic); although used in the apparel and fashion industries, the process has not passed any automotive testing requirements.

Wood

Eucalyptus: One of the fastest-growing species of tree, it is naturally resistant to moisture. It needs 90% less surface finishing than more traditional types of wood used in the auto industry. It is processed without chemicals and the soft texture and natural open pores of the wood remain intact. It is used in BMW’s i3.

Recycling

Bolon Flooring: A Swedish company with a zero-waste philosophy, Bolon works with Italian designer Missoni recycling yarn offcuts and used flooring tiles for product backings. Waste PVC sourced from factories within 250 km (150 miles) of Bolon’s production plant is fused around a cotton yarn and woven to create a uniquely-textured, easily-cleanable and durable surface and the company states that the product is recyclable up to seven times. Currently used for commercial spaces, with the right development to meet automotive testing requirements, it has the potential for automotive use as floormats.

Top Stories

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

How Airbus is Using w-DED to 3D Print Larger Titanium Airplane Parts

INSIDERAerospace

![]() FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

FAA to Replace Aging Network of Ground-Based Radars

NewsUnmanned Systems

![]() Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

Microvision Aquires Luminar, Plans Relationship Restoration, Multi-industry Push

NewsDesign

![]() CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

CES 2026: Bosch is Ready to Bring AI to Your (Likely ICE-powered) Vehicle

NewsSoftware

![]() Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

Accelerating Down the Road to Autonomy

INSIDERManned Systems

![]() Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Can This Self-Healing Composite Make Airplane and Spacecraft Components Last...

Webcasts

Power

![]() Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Hydrogen Engines Are Heating Up for Heavy Duty

Transportation

![]() Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Advantages of Smart Power Distribution Unit Design for Automotive...

Automotive

![]() Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Quiet, Please: NVH Improvement Opportunities in the Early Design...

Power

![]() A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

A FREE Two-Day Event Dedicated to Connected Mobility

Connectivity

![]() E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable Vehicles

E/E Architecture Redefined: Building Smarter, Safer, and Scalable Vehicles

Manufacturing & Prototyping

![]() How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation

How Sift's Unified Observability Platform Accelerates Drone Innovation